In 2024, I went on a journey through Iceland.

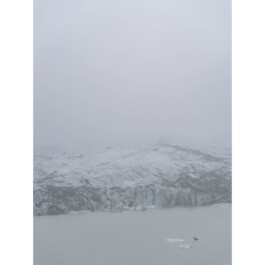

Soon after arriving, I noticed drastic changes in its nature and environment, compared to my previous visits over the last ten years. I realized that Iceland had grown into a well-known and frequently visited place over time. I started to see the country as being overly traveled to, and, in particular, excessively photographed. Apart from cinema or music industry, photographers and content creators “discovered” Iceland for themselves and their audience. This process results in a huge load of produced film-related and photographic material.

I thought that this might have played a part in the development of partial mass tourism in the country. A significant number of people from all over the world come to spend time there, as touched by Iceland’s unique landscapes as I still am. I can relate to people’s needs for capturing their experiences and views by taking pictures. In the end, I’m no different.

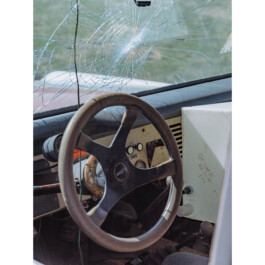

Those drastic changes in the Icelandic environment are probably being imported with the visitors arriving. Accordingly, certain measures seem necessary when dealing with growing numbers of travelers. Several paths and locations have been blocked, certain routes are only accessible when being accompanied by a local guide. Otherwise, people could harm themselves, or nature, or both.

Yet, those are unfortunate changes for travelers who want to experience the country as independently as possible. You cannot roam free any more like you were able to. The thought came to my mind that people are being led to happiness without the possibility of getting to know Iceland at their own pace. After all, most of them are visitors interested in the country from their individual point of view.

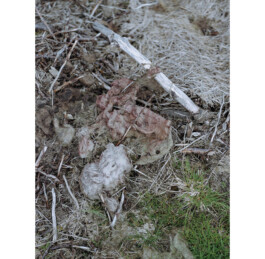

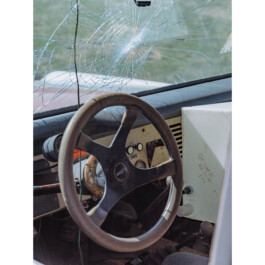

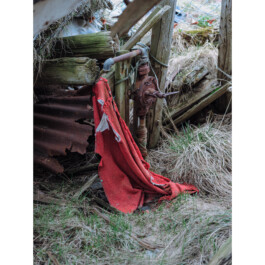

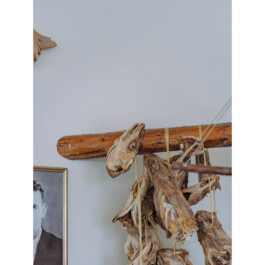

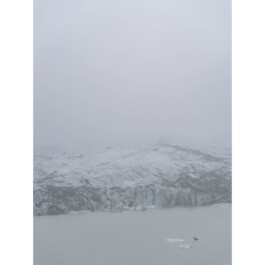

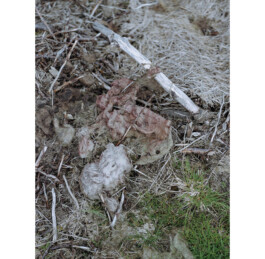

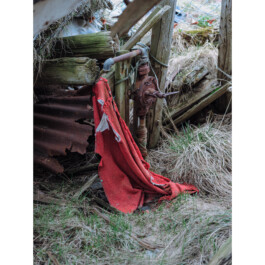

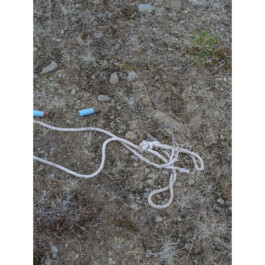

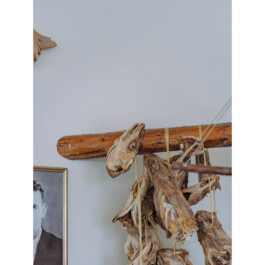

I am aware that I, too, came from another country, observing what was more or less unfamiliar to me. I trod similar roads, carrying my individual mindset and beliefs with me. My impact on Iceland’s environment was like that of other persons: I traveled around, leaving footprints of many kinds. My observations influenced my photographic work profoundly. I decided to take an unusual approach by avoiding to take pictures of famous places. Instead, I changed perspective to become aware of the quieter areas. When I did visit well-known spots, I sometimes literally turned around to take photos of the attraction’s surroundings, not of the attraction itself.

Occasionally, I took a few steps back from famous paths to look at the unseen treasures hiding in the country. Those were conscious steps, some of them to refuse entering a system of stressful mass tourism in an overrun country.

»Ammonia« is about those quiet Icelandic corners, which sometimes felt unknown and surprising to me, but also relatable and familiar. The project focuses on those possibly missed out scenes and unseen objects in relation to each other, merged with my contextual thoughts about their overall surroundings, landscapes and people alike.

In 2024, I went on a journey through Iceland.

Soon after arriving, I noticed drastic changes in its nature and environment, compared to my previous visits over the last ten years. I realized that Iceland had grown into a well-known and frequently visited place over time. I started to see the country as being overly traveled to, and, in particular, excessively photographed. Apart from cinema or music industry, photographers and content creators “discovered” Iceland for themselves and their audience. This process results in a huge load of produced film-related and photographic material.

I thought that this might have played a part in the development of partial mass tourism in the country. A significant number of people from all over the world come to spend time there, as touched by Iceland’s unique landscapes as I still am. I can relate to people’s needs for capturing their experiences and views by taking pictures. In the end, I’m no different.

Those drastic changes in the Icelandic environment are probably being imported with the visitors arriving. Accordingly, certain measures seem necessary when dealing with growing numbers of travelers. Several paths and locations have been blocked, certain routes are only accessible when being accompanied by a local guide. Otherwise, people could harm themselves, or nature, or both.

Yet, those are unfortunate changes for travelers who want to experience the country as independently as possible. You cannot roam free any more like you were able to. The thought came to my mind that people are being led to happiness without the possibility of getting to know Iceland at their own pace. After all, most of them are visitors interested in the country from their individual point of view.

I am aware that I, too, came from another country, observing what was more or less unfamiliar to me. I trod similar roads, carrying my individual mindset and beliefs with me. My impact on Iceland’s environment was like that of other persons: I traveled around, leaving footprints of many kinds. My observations influenced my photographic work profoundly. I decided to take an unusual approach by avoiding to take pictures of famous places. Instead, I changed perspective to become aware of the quieter areas. When I did visit well-known spots, I sometimes literally turned around to take photos of the attraction’s surroundings, not of the attraction itself.

Occasionally, I took a few steps back from famous paths to look at the unseen treasures hiding in the country. Those were conscious steps, some of them to refuse entering a system of stressful mass tourism in an overrun country.

»Ammonia« is about those quiet Icelandic corners, which sometimes felt unknown and surprising to me, but also relatable and familiar. The project focuses on those possibly missed out scenes and unseen objects in relation to each other, merged with my contextual thoughts about their overall surroundings, landscapes and people alike.